By Mark Bertram, Supervisory Wildlife Biologist, Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge

In recent years, you may have seen a Canada lynx, heard of a lynx sighting from a friend or read about one in your local newspaper. Lynx populations have been high in much of Alaska, so they have been out and about. That population high is fueled by snowshoe hares, the primary prey for lynx. Every decade or so, hare populations skyrocket and then crash. Lynx populations follow the same cycle as hares but lag by one or two years. Interestingly, this predator-prey cycle occurs in sync across boreal Alaska.

Dr. Knut Kielland, with the University of Alaska-Fairbanks, has studied this intimate predator-prey relationship since the 1990s. In 2014, he teamed up with Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge to examine a long-standing scientific theory that the peak of the 10-year hare cycle acts in a synchronous “traveling wave” across the Alaskan and Canadian boreal forest, similar to a rippling wave in a pond.

But just what is it that sets the wave in motion and carries it over thousands of miles through the boreal biome? Weather patterns have been suggested, perhaps related to cyclical sunspot activity, but these patterns are inconsistent. The most likely explanation is long distance movements by predators. Both lynx and great horned owls disperse over 700 miles in search of food. Predators moving great distances from food-poor to food-rich areas could explain these 10-year patterns across the landscape.

Photo by Lisa Hupp, FWS

Kanuti, Koyukuk, and Yukon Flats Refuges and Gates of the Arctic National Park and Preserve have since partnered with Dr. Kielland and Tetlin Refuge to collectively examine lynx movements across the northwestern reaches of North America’s expansive boreal forest. Our goal is to identify which habitat characteristics are critical as dispersal corridors so land managers can maintain viable lynx populations across Alaska conservation units. To follow lynx movement, we capture lynx in walk-in live traps and attach a radio collar that records location every 4 hours. Every few days, the collars upload stored locations to a satellite, from which we can subsequently download data.

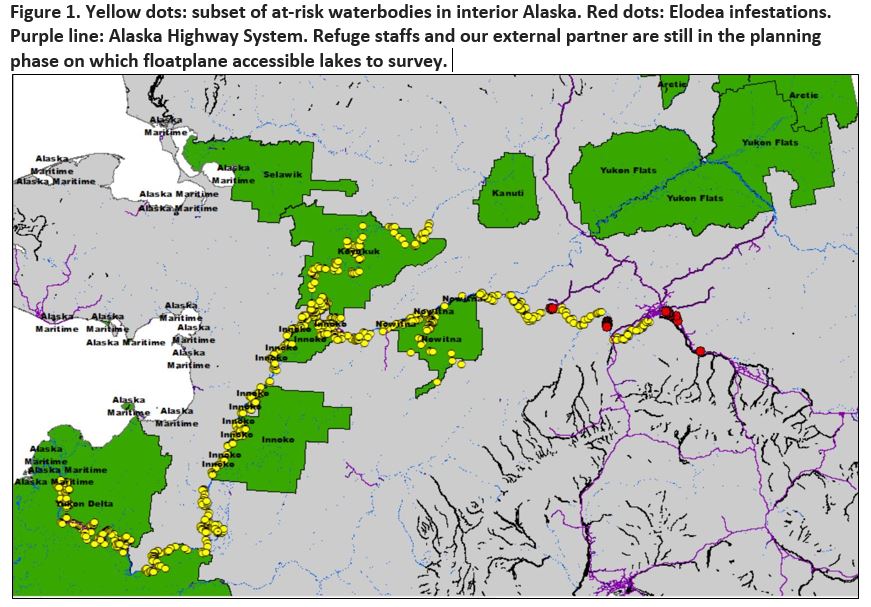

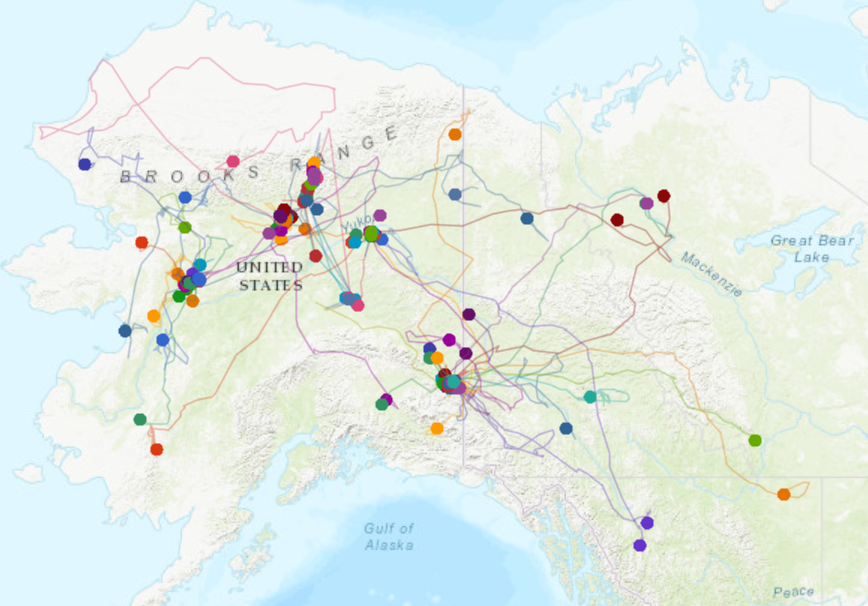

In the past four years, 163 lynx were captured and fitted with radio collars near Tok, Fort Yukon, Bettles, Galena and Wiseman, providing hundreds of thousands of locations. Some lynx stay close to home while others disperse in all directions over great distances (Figure 1). For instance, Tetlin Refuge biologists collared an adult male near Tok in 2017 that took a year-long sojourn through the Yukon and Northwest Territories, eventually settling west of Great Slave Lake, 2,100 miles away! In February 2019, another adult male was collared near Bettles. That April, he headed northwest 550 miles through the Brooks Range to the Chukchi Sea coast near Icy Cape. In May, he beachcombed south for 200 miles, double-backed along the North Slope for 500 miles to the Dalton Highway at the Sagavanirktok River, and then meandered southwest through the Brooks Range. Since October 2019, he has taken a respite in a secluded stretch of the Killik River headwaters.

Movements of 163 telemetered Canada lynx across Alaska and northwestern Canada, 2018-2020

We have recorded long distance dispersals for both young and old, male and female, with daily travel averaging 10 miles and up to 27 miles per day! There appear to be no natural barriers to movement as lynx have trekked across the Brooks and Alaska ranges, and the Wrangell, Cassier and Mackenzie mountains while crossing the formidable waters of the Yukon, Tanana, Porcupine, Copper, Kuskokwim and Mackenzie rivers. Collectively, this collared sample of Alaska lynx from four refuges and one park have traveled from the Chukchi Sea to British Columbia to the North Slope to the Yukon Delta, traversing through 20 conservation areas thus far.

Hare populations are now decreasing across Alaska. In response, we expect more collared lynx will disperse in search of food across the landscape. As more than 1,000 lynx locations are downloaded daily, university, refuge and park biologists will look closely at these dispersal movement patterns in search of terrain that dispersing lynx prefer. Identifying landscape corridors that link conservation units in Alaska and Canada will prove valuable in future land use planning.

Want to learn more and see more stunning lynx photos? Author Mark Bertram will be our speaker at our October membership meeting, October 20 at 5 p.m. on zoom. Put it on your calendar and watch next month’s newsletter and our web site meetings page for the zoom link.