By Poppy Benson, Vice President

Want to do hands on field work? Share your enthusiasm for refuges with visitors? Be a campground host at a very lovely spot? Eight refuges have submitted their wish lists for volunteers and they are now posted on our Current Volunteer Opportunities webpage. Add some wildlife to your summer. Check them out, check your calendar and apply!

There are some intriguing multi week field projects including hare monitoring on Yukon Flats Refuge and biological monitoring and maintenance at Kanuti’s remote cabin. Both these will require some training so talk to them right away to arrange this. Izembek is looking for black brant survey team members but this year they want two. Friends will pay airfare Anchorage to Cold Bay. And that always fun project of banding ducks at Tetlin Refuge for a week is back for a 5th year. Alaska Peninsula Refuge wants help with their visitor center and summer events for the whole summer but two people could split the summer. Airfare, food allowance and refuge housing are provided. Izembek also wants visitor services help but we don’t have money to cover airfare although lodging would be provided. Kenai Refuge needs a campground host at Hidden Lake.

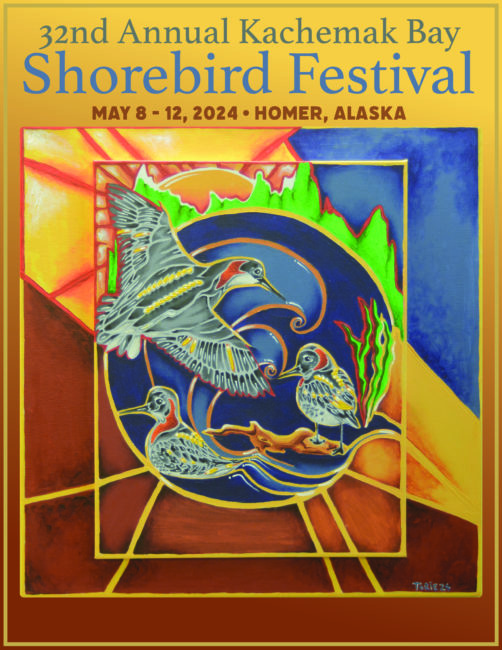

One day or afternoon projects include three big outreach events – the Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival, Seabird Fest and the Kenai Sports and Recreation Show; help with fencing the banks of the Kenai to prevent erosion during the salmon runs; and cleanups on the Alaska Maritime (April 19) and Kenai (date TBD). Friends cosponsors the Shorebird Festival, May 7 – 11 in Homer and volunteers are needed for staffing the Friends Outreach Table and the Birder’s Coffee and for helping the refuge with Festival events. You can sign up for either or both Friends and refuge work. The Festival is our biggest project and traditionally our best source of new members and, it’s really fun! Come on down to Homer and help out. May 3 and 4 is the Kenai Sports and Recreation Show in Soldotna and May 30 – 31 is Seabird Fest in Seward. Friends are needed to help the refuges with activities and education at these events.

You can find all projects listed here including who to talk to for more information. Applications are needed for most projects and you must be a member for most projects. You can join or renew here. In addition, refuges with visitor centers – Kodiak, Kenai, Yukon Delta in Bethel, Alaska Peninsula in King Salmon and the Alaska Maritime in Homer can always use help. Contact those refuges if you live in the area.

Volunteering at the Friends Outreach Booth at the 2023 Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival. We need at least 25 volunteers to cover all 5 days of Festival events and outreach.

I was surprised we got as many projects as we did given the DOGE induced chaos at the refuges – uncertain job futures, stripped staff, credit card use suspended making acquiring field supplies impossible and no budget yet for this fiscal year. Should government uncertainties resolve, I think we would get some more projects so stay tuned to our volunteer current opportunities page.

Most of North America’s seabirds nest on this one refuge and crested auklets are some of the coolest. PC USFWS

Most of North America’s seabirds nest on this one refuge and crested auklets are some of the coolest. PC USFWS

Dan, Mist Netting birds on the river. pc Mark Lindberg

Dan, Mist Netting birds on the river. pc Mark Lindberg

‘

‘