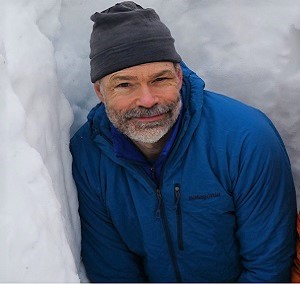

With Dr. Jeremy Littell of the Alaska Climate Adaptation Science Center

This presentation was recorded. View below:Category: Education

Tracking Puffins in the Kodiak Archipelago. 10/18, 5pm-6pm (AKDT)

- In Kodiak, join us for the presentation at the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center with a speaker reception starting at 4:30.

- In Soldotna, a watch party at 5 p.m. at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center on Ski Hill Road followed by volunteer orientation for those interested.

- In Homer, a watch party at 5 p.m. at the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge’s Islands & Ocean Visitor Center followed by an opportunity to join Friends and learn about volunteer opportunities with the Refuges.

Katie Stoner is an Oregon State University PhD student working in collaboration with Kodiak Refuge for her dissertation research assessing the conservation status and threats to Tufted and Horned Puffins breeding in the Kodiak Archipelago within the Gulf of Alaska. She developed a passion for wildlife and birdwatching while attending summer camps with the Audubon Society of Portland in her hometown of Portland, Oregon. She earned her Bachelor of Science degree in Wildlife Biology and Natural Resource Ecology from the University of Vermont. During her undergraduate degree, she had the opportunity to volunteer for Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge on the refuge’s Kittlitz’s Murrelet Nesting Ecology Project, and she used data from her fieldwork on this project to complete her undergraduate thesis.

Katie Stoner is an Oregon State University PhD student working in collaboration with Kodiak Refuge for her dissertation research assessing the conservation status and threats to Tufted and Horned Puffins breeding in the Kodiak Archipelago within the Gulf of Alaska. She developed a passion for wildlife and birdwatching while attending summer camps with the Audubon Society of Portland in her hometown of Portland, Oregon. She earned her Bachelor of Science degree in Wildlife Biology and Natural Resource Ecology from the University of Vermont. During her undergraduate degree, she had the opportunity to volunteer for Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge on the refuge’s Kittlitz’s Murrelet Nesting Ecology Project, and she used data from her fieldwork on this project to complete her undergraduate thesis. After graduating, Katie gained experience studying avian ecology as part of several different research programs. She contributed to the conservation of threatened and endangered petrels and shearwaters in the tropical mountains of Kauai’s Na Pali Coast and monitored tree nests of the Marbled Murrelet in Oregon’s coastal forests. She lived in remote field camps for her work including in the backcountry of the Kodiak Archipelago, on Chowiet Island in the Gulf of Alaska, and on the windy slopes of Cape Crozier on Ross Island, Antarctica studying Adelie Penguins for Point Blue Conservation Science.

Katie is thrilled to return to Alaska and Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge to learn the secrets of Alaska’s “clowns of the seas.”

Life at the end of the continent: geese of Izembek Refuge. 9/20, 5pm-6pm (AKDT)

Presentation by Alison Williams, Widlife Biologist

Izembek National Wildlife Refuge is a remote refuge in southwest Alaska that contains one of the world’s largest eelgrass beds and hosts a huge diversity of wildlife. In particular, the refuge is critical habitat for several iconic Alaskan goose species that rely on the refuge as migratory staging and wintering areas. So why are these geese at Izembek, and where do they come from? How are geese at Izembek affected by changing environmental conditions? Come learn about the life of Alaska’s geese and how Izembek is a key piece of their life history!

Hundreds of thousands of waterfowl, including virtually the entire population of Pacific Black Brant, visit the lagoon to feed on eelgrass and rest during migration. pc: Kristine Sowls/USFWS

Alison Williams is a wildlife biologist at Izembek National Wildlife Refuge, stationed in Cold Bay, Alaska. Originally from Colorado, she grew up in the wild foothills of the Rocky Mountains with a love for wildlife, open spaces, and a special interest in birds. She earned a Bachelor of Science Degree in Wildlife and Wildlands Conservation, before coming to Alaska as a seasonal Biological Science Technician for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Through her work, she spent several remarkable years traveling to various Wildlife Refuges within Alaska, including multiple visits to Izembek, which piqued her interest in seaducks, seabirds, and life on the remote edges of Alaska. She started her current, dream job at Izembek in March 2021, and has enjoyed learning about and seeing the huge diversity of wildlife Izembek has to offer. Alison also recently completed a Master of Science Degree in Avian Sciences from University of California Davis on Common Goldeneye reproductive ecology in interior Alaska

Bird Camp! A Summer Season on Aiktak Island with Sarah and Dan: Tuesday, 4/19, 5–6 pm (AKDT)

Presentation by: Sarah Youngren & Dan Rapp,

Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Biological Technicians

Watch Presentation (Youtube)

Post-presentation Q&A:

There are islands in Alaska where hundreds of thousands of seabirds gather annually to breed. These islands are critical to the survival of these species. Imagine yourself living on one of these islands with one other person. Sound picturesque? It is, but you won’t be spending your days sipping umbrellaed drinks while lounging on the beach. You’re here to do a job. You’re here to collect long-term monitoring data on the seabirds (and other species) that breed on your island. You’re going to be cold, wet, and generally uncomfortable for most of your stay. It’s not an easy life, but it’s worth it. You’ll see and hear things very few ever will. You’ll get to collect data that monitors the health of Alaskan seabird populations and the ocean they, and mankind, depend on for survival. Join Sarah and Dan for a summer field season on Aiktak Island, in the Eastern Aleutians, as biological technicians for the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge. They will show you what it takes to work in this rugged and remote refuge.

Sarah Youngren and Dan Rapp are seabird researchers. Most people have no idea what they do, because they work where very few people go and with species that spend most of their lives at sea (or in these places few people get to go). Between Sarah and Dan, they have 28 years of experience working with seabirds on remote islands in Alaska and Hawaii (and a stint in Louisiana). They both started their professional careers working with Alaskan salmon, and dabbled in other fieldwork, but both eventually found their way to a remote seabird colony. All parts of living and working on these islands spoke to them, and their addiction hasn’t let up. They have worked with a plethora of seabird species, ranging in size from the armful Black-footed albatross, to the fit in your palm Leaches storm-petrel. Most of the data they collect contributes to long-term datasets for the purpose of detecting trends / changes within seabird populations. But they also conduct and participate in original research, most recently they helped outfit albatross with tags to track their movements across the North Pacific from their breeding colony at Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge. Both Sarah and Dan earned their Masters degrees in marine science from Hawaii Pacific University in 2015, with theses that addressed patterns and impacts of plastic ingestion in Hawaiian seabirds. After completing their graduate work, they returned to seasonal fieldwork. Since 2015 they have been spending summers working for Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, specifically on Aiktak Island in the Eastern Aleutians.

Bears, the Emerald Isle and Bear Biology in Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge: Tuesday, 3/15, 5 – 6 p.m. (AKDT)

This meeting’s presentations were recorded. Watch below:

Arctic Refuge Video

Dr. Joy Erlenbach, Kodiak Refuge Bear Biologist

Have you ever wondered what a bear biologist actually does? Get a tour of the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge—see the lush green landscapes, the jagged peaks, the idyllic remote streams, the majestic bears and wildlife…and get to know the bears of Kodiak just a little bit better. Find out what the refuge has to offer, and the ways our biologists work to maintain the land and resources for future generations. Listen as Joy shares with us what it’s like to be a bear biologist at Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge— the work she does, the needs of bears, and future directions for bear biology and management in Kodiak.

Protected ocean waters within a fjord, the surface of Three Saints Bay reflects mountains like the surface of a calm lake. pc: Robin Corcoran.

Protected ocean waters within a fjord, the surface of Three Saints Bay reflects mountains like the surface of a calm lake. pc: Robin Corcoran.Joy Erlenbach says she became interested in bears because of the adaptability of bears—their ability to adjust to myriad challenges and still succeed—as well as their misunderstood nature. Joy has studied black, brown, and polar bears but brown bears are her favorite because of their big personalities and grit.

Joy has been Kodiak Refuge’s bear biologist since March 2020. Prior to working for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service she was a Postdoc, PhD Student, and Masters student at Washington State University where she studied nutritional ecology of Alaskan brown bears, optimal diets for brown bears in the wild and captivity, and energetics of polar bears on land. She did extensive field work in Katmai National Park from 2015 to 2018 for her PhD as well as short stints for other projects on the Kenai Peninsula and the Kotzebue area. She has also done field work in Canada, Yellowstone, and California. She has been involved in 15 scientific papers including her PhD thesis, Nutritional and Landscape Ecology of Brown Bears in Katmai National Park, Alaska.

“One of my favorite memories during some of my work was watching a young wolf and a young brown bear play tag on the intertidal. That and the time the same young bear recognized how bad she was at fishing and gave up and just lazy-river floated down the river instead.”

In addition to job skills such as collaborative research planning, data and statistical analysis, and population monitoring, Joy’s resume includes unusual skills such as capturing large wildlife by helicopter darting, aerial netting and snares, planning remote field research camps and projects, backcountry navigation and radio telemetry.

An Eye to the Future: Stewarding the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge: Tuesday, 2/15, 5 – 6 p.m. (AKT)

Kris Inman, Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Supervisory Wildlife Biologist

This meeting’s presentations were recorded. Watch below:

Christina Nelson, Selawik National Wildlife Refuge:

Intro to Selawik

Kris Inman, Kenai National Wildlife Refuge:

Stewarding the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge

(This recording has been edited to include the wolverine footage that wouldn’t play during Kris’ presentation.)

This is a time of unprecedented, profound, and rapid human-driven environmental change. In her presentation, Kris will share a few of the Kenai biology team’s many projects that give a big-picture view of how wildlife populations and habitats might be changing or impacted by landscape issues like climate change and human population growth. Changing water temperatures in salmon streams, increased traffic on the Sterling Highway, more people living and recreating around the refuge and the spread of non-native species are a few of the human caused impacts to the refuge wildlife that Kenai biologists and agency partners are addressing.

Kris will share new technology like thermal imagery to document and understand the impact of water temperature changes on our world-famous salmon rivers that sustain bears, eagles, and people. She will also share results from the Refuge’s efforts to minimize the impact of increased human presence on the Kenai including the effectiveness of Alaska’s first wildlife road crossing project to provide safe movements for wildlife across the busy Sterling Highway which splits the Refuge. She will also highlight collaborative efforts to eradicate or control the spread of non-native invasive species like pike, elodea, white sweet clover, bird vetch, and reed canary grass that influences salmon habitat or encroach on native vegetation. In doing so, the biology team, working with refuge staff and many partners, will meet the station’s vision of stewarding the lands and waters with an eye to the future, so the Refuge’s diverse and abundant wildlife remain for the enjoyment and well-being of generations to come.

Moose using the new Sterling Highway wildlife underpasses. Fences funnel wildlife to the underpasses of this increasingly busy highway. Kris will discuss what the refuge has learned about the effectiveness of this project.

Kris Inman recently joined the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge as the Supervisory Wildlife Biologist. Before coming to Alaska, she worked on a wide range of wildlife research and inventory and monitoring projects, from the little-known Tomah mayfly and freshwater mussels to more charismatic species like wolves, bears, and wolverine. Kris received a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Maine and a Master of Science degree from Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

She spent the last twenty years living, working, and raising her family in the lands outside of Yellowstone National Park, where she and her husband co-led a collaborative wolverine research study for the Wildlife Conservation Society. This project eventually would contribute the largest body of science on wolverines in the lower 48 and would identify the biggest conservation needs: to restore, connect, and monitor wolverines across their current and historic range.

From there, Kris switched from researcher to implementor. She worked with broad stakeholder groups in SW Montana to apply wolverine science in a region critical to wildlife connectivity for not only wolverines but also migratory ungulates and recovered grizzly bear and wolf populations. As the Coordinator of Strategic Partnerships and Engagement for the Wildlife Conservation Society, she brought stakeholders together to develop tools to reduce negative human-wildlife interactions. She also explored and implemented natural climate adaptation strategies like beaver mimicry to improve private working ranchlands’ economic and ecological sustainability as critical corridors to public lands.

Kris holding a wolverine!

In 2018, the Disney Conservation Fund named Kris a Disney Conservation Hero for her contributions to science and engaging and empowering communities to take science to action. Kris was also selected as an American Association for the Advancement of Science IF/THEN® Ambassador, a network of 125 women STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) professionals from around the country who share their professional stories so young girls see that a career in STEM is possible.

Kris sees the Kenai Peninsula as similar to the Greater Yellowstone Area in its global significance as a large, intact, wild landscape, diverse in its wildlife while grappling with the challenges of rapidly growing nearby communities seeking solitude and world-renowned outdoor experiences.

Kris is glad to be a part of the Kenai Refuge and the larger refuge team in Alaska. She works with colleagues who recognize that conserving these great places will take a new future-oriented approach to conservation, and they are committed to developing solutions to meet the challenges of this century. At the same time, this work recognizes that people are part of nature and not separate from it. Seeing people in this light, we no longer just identify people as the problem but also the solution.

Bridging the Gap/Usguciaraq: Tuesday, 1/18, 5 – 6 p.m. (AKT)

This meeting’s presentation was recorded: watch below.

This recording does not include Jacqueline Cleveland’s video (not yet released).

Christopher Tulik of the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge and Jacqueline Cleveland of the Togiak National Wildlife Refuge, both Yupik, will present on their work as Refuge Information Technicians (RITs). Christopher’s intimate knowledge of the Yupiaq language and culture, the local area and the people make him a valuable liaison between the Refuge and those who live in the communities on and around the Yukon Delta Refuge. He travels by boat, snowmachine and plane to make personal visits to dozens of small subsistence communities. During the visits, he informs residents about Refuge-related conservation work, hunting and fishing opportunities, and other topics that are important to subsistence harvest. He also hears their concerns and local knowledge of fish and wildlife matters and ensures this is communicated to Refuge staff back at refuge headquarters. Jacki is new to her role as an RIT for Togiak National Wildlife Refuge. She will share with us the essence of subsistence life in her village of Quinhagak through her outstanding photography and videography.

Jacqueline with sauropod dinosaur tracks on the Togiak Refuge.

Christopher Tulik was born in Bethel and raised in Nightmute, a small village on Nelson Island along the western Bering Sea coast of the refuge. Growing up in a traditional subsistence lifestyle has given Christopher an understanding of the importance of fish and wildlife to the culture of local Alaska Native people. Christopher has said he became interested in working with wildlife when he was very young and became aware of the fish and wildlife all around him that sustained his family in all seasons. He learned respect for nature from watching his father and older brothers returning from the hunt and how the catch had been properly handled. Christopher Tulik

Christopher Tulik

He was one of the youngest Refuge Information Technicians (RITs) hired when the program began in 1984. After a break, he returned to serve as an RIT in 2014 to assist the Refuge with outreach, education and tribal consultation. Christopher Tulik recently accepted a position as the Lead Refuge Information Technician (RIT) for the Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge. In this position Chris will supervise up to five permanent RITs. You can read more about Chris’s life and work here.

Nalikutaar (in Yup’ik) or Jacqueline Cleveland was raised in Quinhagak, Alaska where she currently lives with her fiancé, Franko and dog, Pumba. Jacki received her Bachelor of Art’s degree from Montana State University in Media and Theatre Arts and Native American Studies. She is a subsistence hunter, fisher and gatherer, a freelance photographer/videographer, and recently accepted the job of Refuge Information Technician for the Togiak National Wildlife Refuge.

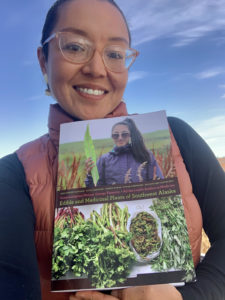

Jacqueline Cleveland with the book that features her photographs.

Jacqueline Cleveland with the book that features her photographs.

Jacki has had her photographs published in numerous publications most notably in the 2020 book from the University of Alaska Fairbanks press, Yungcautnguuq Nunam Qainga Tamarmi/All the Land’s Surface is Medicine: Edible and Medicinal Plants of Southwest Alaska, for which she did most of the photography. Jacki recently completed a film project with BBC on Nelson Island in which she served as location manager. The segment on muskox in rut filmed on the island will be part of the Earth’s Great Rivers II to be out this spring on BBC. Jackie is currently finishing up work on a film about climate change that she co-directed, served as cultural advisor for, as well as did some of the filming. Ellavut Cimirtuq/Our World is Changing will also be out this spring.

No meeting in December but we’ve got a great line-up for next year!

Come join us and learn more about refuges and wildlife at our 7 meetings per year held from 5-6 pm, on the 3rd Tuesday of January, February, March, April, September, October and November of 2022. We take the summer and holiday months off. Presenters share first-hand experiences, current issues, conservation threats and great stories.

Upcoming Presenters:

- January 18: Bridging the Gap/Manigtengnaqsaraq: Native Alaskans employed as Refuge Information Technicians are the connection between villages and refuge management; presented by Christopher Tulik from Yukon Delta Refuge and Jacki Cleveland from Togiak Refuge.

- February 15: An Eye to the Future: How the Kenai Refuge is preparing for climate and landscape change with supervisory biologist Kristine Inman.

- March 15: Kodiak Refuge Bears

- April 19: Bird Camp! Alone on an Aleutian Island with 100,000 seabirds with Sarah Youngren and Daniel Rapp of the Alaska Maritime Refuge

You can always hop on the Friends website to view any presentation that you miss: recordings here

My Time among the Peregrine Falcons: Tuesday November 16, 2021, 5pm AKT

Presentation recorded on Tuesday, November 16, 2021

Fran Mauer, Arctic Refuge Senior Biologist, retired

Fran Mauer started his career in Alaska 50 years ago at a pivotal point in wildlife conservation. He worked on some of the most high-profile projects such as the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) and evaluating the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge 1002 area for likely impacts of oil development. After that exciting and controversial work, Fran got off the hot seat in 1988 to spend the next 14 years surveying Peregrine Falcons on the Porcupine River. This annual survey of nesting falcons was necessitated by their endangered status as a result of DDT exposure in the lower 48, as well as in Central and South America. Fran will tell us the story of this bird’s recovery and what he learned from this work about the interconnectedness of the Porcupine country with the rest of the Arctic Refuge, adjacent Canada and beyond. He will also describe some of the interesting geological history that created the Peregrine habitat and share human stories of the Porcupine River region including some unexpected discoveries.

Porcupine River by Callie Gesmundo

Fran Mauer has a BS degree in Wildlife biology from South Dakota State University and a MS degree in Zoology from the University of Alaska – Fairbanks. He served two years in the US Army as a med lab technician during the VietNam war, before arriving in Alaska.

He started with the Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) as a seasonal bio-tech in 1974 to help identify salmon habitat that may be affected by the Chena River Flood Control Project but quickly landed his first permanent position with the Service working for the Western Alaska Ecological Service office in Anchorage. One of his earliest assignments was to identify potential effects of the proposed Bradley Lake hydropower project. In 1976, Fran joined the FWS Alaska planning team which provided resource information to guide the Congressional process underway to establish new National Wildlife Refuges, National Parks, Wild Rivers and Wilderness designations in Alaska. Fran covered the northwest and arctic areas of Alaska which got him involved with the prospect of expanding the Arctic National Wildlife Range, as well as the controversy over potential oil development on the coastal plain and wilderness protection.

Following passage of ANILCA in 1980, Fran joined the staff of the Arctic Refuge as a field biologist and became involved with the Congressionally mandated “1002” studies of the coastal plain. His primary work involved an inter-agency baseline study of neonatal calf mortality on the calving grounds of the Porcupine caribou herd for the purpose of predicting what impact oil development might have on the caribou. During 1988 to 2001 his work expanded to include Dall Sheep, moose, peregrine falcons and other birds of prey. Fran served as a senior biologist at the Arctic Refuge for 21 years.

Fran has authored several scientific papers, governmental reports and essays for books and magazines. Fran’s essay “Our Geography of Hope ” about an imaginary walk across the Arctic Refuge from north to south was featured in Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: Seasons of Life and Land: A Photographic Portrait by Subhankar Banerjee. This 2003 book may have been instrumental in holding off the leasing threat to the refuge at that time. A just published book, Defending the Arctic Refuge by Finis Dunaway, devotes a chapter entitled “Science and Skulduggery” to Fran’s and also co-worker Pam Miller’s experiences in getting the correct data on expected oil development impacts on wildlife to Congress in spite of data suppression and the doctoring of Fran’s caribou calving information at high levels. The data doctoring led to a new role for Fran – whistleblower!

Following retirement in 2002, Fran has served on the board of Wilderness Watch and represented its Alaska chapter. He lives in Fairbanks and continues to advocate for maintaining the ecological integrity and the wilderness character of our Alaska National Wildlife Refuges and National Parks.

Suggested reading:

Ambrose, S., C. Florian, R.J. Ritchie, D. Payer, and R.M. O’Brien. 2016. Recovery of American peregrine falcons along the upper Yukon River, Alaska. Journal of Wildlife Management.

Ager, T. 1994. Prehistoric Alaska. Alaska Geographic Vol. 21, No. 4. Pages 38-53.

Thorson, R.M. and E.J. Dixon. 1983. Alluvial history of the Porcupine River, Alaska: role of glacial-lake overflow from northwest Canada. Geological Society of America. Vol.94: 576-589.

Carson, R. 1962. Silent Spring. Fawcett Publications Inc. Greenwich, Conn.

Murie, Margaret E. 1997. Two in the Far North (part three: The Old Crow River pages 209-255). Alaska Northwest Books, Portland, OR.

Richard Martin. 1993. Kaiiroondak (Behind the Willows). Publications Center, Center for Cross-Cultural Studies, Univ. of Alaska, Fairbanks.

People of the Lakes, Stories of Our Van Tat Gwich’n Elders. 2009. Univ. of Alberta Press, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Mauer, F.J. 1998. Moose migration: northeastern Alaska to northwestern Yukon Territory, Canada. Alces Vol. 34(1): 75-81.

Tuesday October 19, 2021, 5pm AKDT

From Caribou Corrals to Seaplane Hangars: A Cultural Resources Overview of Alaska’s National Wildlife Refuges

Tuesday, October 19, 2021, 5-6pm (AKDT)

Jeremy Karchut, Regional Archaeologist/Regional Historic Preservation Officer USFWS, Alaska Region

Join us to discover the rich cultural and historic legacy of Alaska’s Refuges. Jeremy Karchut will provide an overview of the refuges’ vast array of cultural resources representing 14,000 years of human history. Sites range from those associated with the earliest humans to set foot in North America to mid-20th century aircraft hangars. Prehistoric archaeological sites in the Arctic, rock art on the Kodiak coast, historic cabins on the Kenai Peninsula, WWII battlefield sites in the Aleutians, and historic Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) facilities critical to the agency’s Alaska mission are some of the cultural resources to be highlighted in this talk.

The FWS recognizes cultural resources as fragile, irreplaceable assets with potential public and scientific uses, representing an important and integral part of the heritage of our Nation and descendant communities. It is FWS policy to identify, protect, and manage cultural resources located on refuge lands. Jeremy will consider some of the challenges and rewards of managing these nonrenewable resources in an era of rapid environmental change and include highlights of key federal historic preservation legislation.

B-24D Liberator Bomber that crashed in 1942 on Atka Island, in what is now part of the Alaska Maritime NWR. Photo by Steve Hillebrand, USFWS.

Jeremy is the FWS Regional Archaeologist in Anchorage. He is interested in high altitude and high latitude archaeology and for more than 20 years he’s been involved with projects focusing on the effects of climate change on archaeological resources and what archaeology can teach us about how humans adapted to environmental change in the past. Jeremy is a native of Colorado, having earned a BA in Anthropology from Fort Lewis College, Durango in 1998, and a MA in Archaeology and Ancient History from University of Leicester, UK in 2003. He has served as a federal archaeologist since 1995, including with the US Forest Service and the National Park Service in the US Southwest, Central and Southern Rocky Mountains, Great Plains, and 12 years in Alaska.

This presentation was recorded; view below.