28th Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival

By Matt Bowser, Entomologist at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge

In September 2018, we hosted two earthworm experts from the University of Minnesota at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. Dr. Kyungsoo Yoo and graduate student Adrian Wackett study how earthworms alter soils in the American Midwest and northern Europe, places where exotic earthworms have been around for a long time. In Alaska, with the possible exception of one species, all earthworms have been recently introduced. The Kenai Peninsula offered these scientists a chance to study incipient populations of earthworms that we had documented just a few years ago. To read the report, click here.

They chose to work at Stormy Lake in Nikiski, where nightcrawlers were dumped near the public boat launch. Nightcrawlers (Lumbricus spp.) make vertical burrows and feed on surface litter, changing soils more dramatically than other earthworm species introduced to our area. Adrian and Dr. Yoo remarked they had never seen such abundant nightcrawlers as what they saw at Stormy Lake. Earthworm biomass was twice as high as anything published online. Using their data, I estimated 1,300 pounds of earthworms per acre at Stormy Lake. To put this in perspective, a 1,300-pound moose needs ~500 acres in good habitat. So earthworms can outweigh moose by 500 times on an acre of boreal forest!

Photo: University of Minnesota graduate student Adrian Wackett digs a soil core near a public boat launch on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge to examine the effects of a recent introduction of nightcrawlers

Why do earthworms flourish here? We suspect a bountiful food supply of leaf litter with little competition from other worm species. We also witnessed a new phenomenon. As the nightcrawlers invaded new areas, they buried the leaf litter with mineral soil brought up from below. In areas with older infestations where nightcrawlers had more time to multiply, they had consumed all litter and humus layers.

You have likely heard that earthworms improve garden soils. This is true—cultivated plants generally benefit from earthworms. But not everyone in the natural ecological community wins. Exotic earthworms have caused problems in other parts of northern North America. By fundamentally changing the structure and properties of soils through their feeding, introduced earthworms have caused declines in native plants, fungi and animals that depend on thick leaf litter. Ferns, orchids and shrews, for example, tend to do poorly where earthworms occur while grasses and exotic plants fare better. Earthworms can even change which tree species repopulate a forest by altering seed and seedling survival. Thankfully, nightcrawlers remain absent from most of the Kenai Peninsula. On the Kenai Refuge, nightcrawlers are found only at a few boat launches, the result of what is termed “bait abandonment.”

On their own, nightcrawlers spread more slowly than most glaciers move. It would take five centuries for them to colonize Stormy Lake’s shoreline. Robins and other birds could transport earthworms, but this is an unlikely vector. Nightcrawlers sexually reproduce, which means robins would have to drop multiple live nightcrawlers in the same vicinity to start a new population. Even if this did occur, robins tend to carry food only short distances, so this transport medium would not greatly accelerate dispersal rates. Earthworms can disperse faster by streams, but almost all their known long-range dispersal has been by people.

Here on the Kenai Refuge and in Alaska generally, where nightcrawlers arrived only recently, we still have a chance to conserve naturally diverse and naturally functioning forest ecosystems. In Canada and some northern U.S. states, organizations and governmental entities have sought to change people’s behavior by educating them about problems caused by exotic earthworms. Voyageurs National Park in Minnesota took it a step further by prohibiting live bait partly to prevent the spread of invasive earthworms. These public outreach efforts and regulations may reduce the long-range spread of exotic earthworms, but people continue to transport earthworms to new areas. We are currently assessing the potential for pesticides tested at airports and golf courses to eradicate small populations of nightcrawlers.

Pat Walsh has been Supervisory Fish and Wildlife Biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Togiak National Wildlife Refuge since 2001. He has BS and MS degrees in wildlife ecology and 30 years of experience in leading ecological studies.

To join the meeting: Join the Zoom meeting by computer

OR

Join by phone:

Phone number: (669) 900-9128

Meeting ID: 918 6891 5432

Password: 336354

Download the presentation: Togiak Refuge presentation for Refuge Friends April 2020

The meeting will also be recorded and available here if you miss the 5 p.m. live meeting.

The Friends of Alaska National Wildlife Refuges and the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge have decided that for the health and safety of our community, employees, volunteers, and visitors during the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak, the Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival will not proceed as planned in early May.

It takes an entire community to support Alaska’s largest, most accessible wildlife viewing opportunity, and we are grateful to have earned the community of Homer’s support for the past 28 years. It is out of care and respect for the community (and our many beloved birders), and in keeping with guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Alaska’s Chief Medical Officer, that we take this action.

We know people across Alaska and around the world will miss the event, and the festival planning committee is saddened to share this news, but we are committed to doing our part to slow the spread of this dangerous virus.

While we are not gathering together this year, we plan to return better than ever in 2021. We also find hope in our shorebirds – as they migrate north, they will continue to gather along our shores. Please stay tuned for new ways to connect with the Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival.

Thank you for your patience and understanding. As you continue to enjoy Alaska’s wildlife and wild places, please practice safe social distancing.

How will wildfire affect refuges in a changing climate? Wildfire was always a major driver of habitat change in much of Alaska but last summer was one for the record books in terms of the number of people impacted by smoke, road closings, activity cancellations and fear for life and property. Scientists and managers are scrambling to understand what Alaska will look like in the future with predicted increases in fire occurrence and to figure out how to manage fire with a changing climate. Lisa will give an overview on fire in Alaska from fire history and habitat changes to current research topics and refuge projects to reduce risks.

Lisa’s current work focuses on post-fire effects on wildlife and vegetation, burn severity and fuel treatment planning and monitoring. She is a collaborator on research on climate change and fire in boreal forest and tundra and on modeling fire behavior during wildfires. After working on the Selawik, Koyukuk/Nowitna, Yukon Delta and Kanuti refuges, she was hired in her current position as fire ecologist for all Alaska refuges in 2010. Lisa began her Alaska career as a Master’s student at UAF in 1989 investigating the effects of tundra fire on caribou winter range.

By John Morton, retired USFWS biologist

I called Pat Walsh, the Supervisory Biologist at Togiak National Wildlife Refuge, to ask him about an interesting article he published this past year in the journal Rangifer. Titled “Influence of wolf predation on population momentum of the Nushagak Peninsula caribou herd, southwestern Alaska”, it essentially asks if wolf predation can be good for caribou.

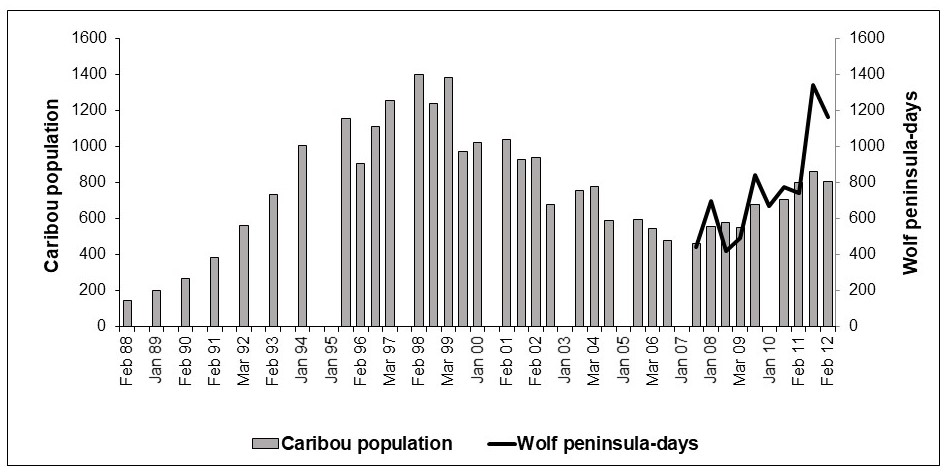

Walsh laid out a fascinating ecological story. During 1997−2007, the nonmigratory caribou herd on the Nushagak Peninsula, located within Togiak Refuge, declined from 1,400 to 500 individuals. Walsh, working closely with his Alaska Department of Fish and Game State colleague, James Woolington, investigated the time budgets of three wolf packs that used the peninsula during the following five years (2007−2012) to figure out if wolves were responsible for the herd’s decline. During their study, wolf predation steadily increased on the caribou; however, contrary to expectations, the caribou population steadily increased as well!

These two field biologists tracked 20 GPS- and VHF-collared wolves during their study. They found that only one of three packs regularly used the peninsula. This pack, known as the Ualik Lake pack, spent 35% of its time there. Its use of the peninsula was disproportionately high in late summer and fall, disproportionately low in winter, and proportional during the caribou calving season in early summer. The overall wolf use of the Nushagak Peninsula increased in direct response to increasing caribou abundance. Walsh and Woolington concluded that, in this instance, wolf predation was not driving caribou population dynamics. Instead, the caribou population was the driver and wolves were simply responding to an increasingly abundant food. The Nushagak herd had previously declined, then increased, due to internal demographic factors apparently unrelated to predation (see graph).

Not all wolf-caribou interactions are the same, and that the geography of the Nushagak Peninsula makes this situation somewhat unique. The 800 mile2 peninsula is narrow enough that this single wolf pack was able to establish its territory near the head of the peninsula, and thus defend the area from other wolves on the mainland. So, as the Nushagak caribou population increased, the Ualik Lake wolf pack spent more time preying on them, and concurrently (and ironically) spent more time protecting them from predation by other wolves! Life is not always as it seems.

Since the conclusion of their study in 2012, the caribou population has continued to increase to the point that habitat damage is evident. In short, high numbers of caribou may be eating themselves out of house and home. Wildlife managers have attempted to address this by increasing human harvest through several regulatory changes, but lack of snow in recent winters has prevented snowmachine access, which is the primary transport used by hunters there. Walsh told me, “We think it’s possible that the Nushagak Peninsula caribou will face winter food shortages in the near future, and may simply walk away”. Should this happen, local villages could lose an important subsistence resource.

Although wolf predation has not served as a very effective population control for caribou, it is certainly working in the direction of management. And to answer the question as to whether wolves can be beneficial for caribou, it appears that in this case, it could be that the protection resident wolves provide may be too much. As Walsh sees it, a bit more predation might prevent degradation of caribou habitat, which could help sustain the caribou population itself.

Walsh and Woolington wrote that the principal reason they conducted their study was to assess whether wolf population control was necessary to prevent the population decline in this herd. Had predator control been instituted at the onset of this study (as requested by local management committees), it is reasonable to believe that the caribou population would have increased as it did. However, these two seasoned biologists also point out “stakeholders might have incorrectly concluded that wolf control caused the caribou population response.” This case illustrates the importance of careful thought and having sufficient data for both ungulate and predator populations before invoking predator control.

Lisa will be speaking to us at the Anchorage meeting: our other gatherings will join via Zoom Meetings or you can join from home (see below).

Lisa Hupp will share her experiences behind the lens photographing Alaska’s refuges. “I love how photography can demand close attention and devotion to place,” Hupp says. “It’s a way to see and share the world, whether you take photos on a phone or with a backpack full of equipment. Alaska’s national wildlife refuges are places of endless possibility for photographers, from dramatic and vast landscapes to charismatic wildlife. These refuges are big, wild and remote; photography can help us to tell their stories.”

Hupp is the Communications Coordinator for National Wildlife Refuges in Alaska. You can see some of her images and read how she gets those amazing shots here.

Download Lisa’s presentation: Arctic to Attu (PowerPoint .pptx file)

Missed the meeting? Watch a recording of the meeting below:

By: David Raskin, Friends Board President The calm before the storm! The Arctic Refuge drilling proposal continues front and center on the national stage, and the administration’s numerous assaults on the environment continue to be bogged down under the pressures of time, resources, and inadequate scientific studies. However, we expect major events in the very near future.

The calm before the storm! The Arctic Refuge drilling proposal continues front and center on the national stage, and the administration’s numerous assaults on the environment continue to be bogged down under the pressures of time, resources, and inadequate scientific studies. However, we expect major events in the very near future.

Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

There are rumors concerning DOI plans to sell leases for oil and gas development in the Coastal Plain of the Arctic Refuge. The Record of Decision (ROD) continues to be delayed for unannounced reasons and is now expected sometime in March. Since the lease sale had been planned for December 2019, the delay of the ROD and the necessary waiting periods after its release have pushed any possible lease sale farther into the Spring at the earliest.

There is no word about plans for seismic exploration. which likely cannot occur before the 2020-21 winter, if at all. However, SAExploration has been sold to a Norwegian company. The implication of this transfer for exploration in the Coastal Plain is unclear.

Our conservation and Native Alaskan partners continue to hold more successful outreach events throughout the country, and there have been many great pieces in various media. The campaign’s meetings with executives of oil companies and financial institutions concerning the dangers of Arctic drilling and the financial risks of supporting such efforts are producing impressive results. Bernadette Demientieff, Executive Director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee, and the Arctic Refuge Defense Campaign continue to spearhead this increasingly successful campaign. Major investment managers and banks are joining the ranks of those warning against investing in oil and gas projects, with special attention to the Arctic. We continue to make progress in the decades-long battle to save and preserve the Arctic Refuge and its subsistence and cultural values!

Izembek National Wildlife Refuge

There was no significant development in the suit filed on August 7, 2019 in federal district court that names Friends as the lead plaintiff along with eight conservation partners. The Court approved the unopposed intervention of the State of Alaska. We have not received a ruling from the Court, and we will provide updates as this lawsuit works its way through the legal process.

Kenai Predator Control and Hunting Regulations

The proposed Kenai Refuge predator control regulations have not been released, but we continue to expect them soon. It is likely that the new regulations will not only allow hunting of brown bears over bait, as well as loosened restrictions on hunting in the Skilak Wildlife Recreation Area and 4-wheel drive access to frozen lakes, but we expect additional draconian measures to be included in the final version. It appears that there will be a 60-day comment period, but no public hearings. All of our conservation partners are closely monitoring this process and are preparing to take whatever action is necessary to stop this assault on Kenai Refuge wildlife.

Ambler Road

We are not aware of any significant development on the proposed 211-mile long Ambler industrial road even though it is on an “unprecedented, extreme fast track,” according to a BLM official.

Friends of Alaska National Wildlife Refuges is working hard to get some volunteer opportunities for our members. The refuges are submitting requests for volunteers and funding during January. At our February Board meeting, we will be approving as many of their requests as possible. Any Volunteer Opportunities for 2020 will then be listed on our website by February 16 so stay tuned!

Meanwhile there are other opportunities to offer your skills and knowledge by contacting a refuge directly. These projects are not a part of Friends, but are general ongoing needs of various refuges. Below is a list provided by Yukon Flats. There will be others of this type on more refuges and when we have information, we’ll try to get it out to you. Contact Jimmy_fox@fws.gov directly if interested.

· Continue lynx capture/monitoring/snowshoe hare monitoring project

· Conduct mallard banding project at Canvasback Lake

· Implement annual scoter and scaup aerial survey

· Conduct annual waterfowl brood surveys

· Operate trail camera and snow monitoring program

· Conduct annual stick nest survey and keep active nest locations in NIFC Known Sites Database

· Implement annual loon survey

· Conduct annual trumpeter swan survey

· Implement annual Dall’s sheep survey in the White Mtns

· Provide aerial survey support for Draanjik River sheefish research project (2020-2022)

· Support Elodea eradication efforts in the Interior

· Conduct invasive species surveys in villages after consultation with tribes

· Inspect John Herbert’s Village structures, make necessary repairs, and identify deferred maintenance needs; and develop interpretative panel to display on site

· Engage students and create entries for the USFWS Migratory Bird Calendar in Fort Yukon

· Staff Outdoor Days event at UAF in Fairbanks

· Staff Bird Watch event at Creamer’s Refuge in Fairbanks

· Conduct USFWS waterfowl hunting clinic in Birch Creek

· Create salmon art and conduct fish wheel decoration contest

· Staff the USFWS Dragonfly Days event in Fairbanks

· Conduct an event in association with the 4th of July Parade in Fort Yukon

· Staff the Golden Days Parade float in Fairbanks

· Engage students at career fairs in Fort Yukon

· Participate in, and support, the National Native Youth Congress

· Revise fire ecology language for Web page and other outreach materials

· Create new content for kiosks in Circle and Fort Yukon

· Assess condition of kiosks and panels at Dalton Highway MP86 and Yukon River Crossing

· Work with tribes to install invasives prevention signs at major points of entry

· Investigate purpose and feasibility of marketing, in partnership with others, the LEO Network

· Develop refuge staff poster for rural communities

· Create and distribute biological reports to villages and post highlights on Web site and Facebook

· Work with IARC to develop messages for joint outreach materials and efforts

· Finalize, print and distribute new refuge brochure (and replace stock on shelves)

· Create and distribute CATG/USFWS fact sheet about AFA

· Conduct routine maintenance at Scoter Lake Fueling Site and other avgas tanks

· Continue to oversee and assist with construction of Fort Yukon bunkhouse

· Contract and administer construction of fence and gates for Fort Yukon bunkhouse

· Develop contracts for construction of solar systems for Fort Yukon Warehouse, Bunkhouse and Fairbanks Hangar

· Contract for insulating the Fort Yukon warehouse

· Repair roof on Canvasback Lake cabin

· Develop use policies for Fort Yukon facilities and equipment (and distribute/post)

· Develop calendar of routine maintenance for all assets

· Perform routine cleaning of Fort Yukon cabin and outhouse and keep essentials stocked

· Replace fuel meter and access system on hangar av gas tank

· Compile hangar repairs task order for Maintenance Action Team

· Maintain all field equipment