This meeting was held on Tuesday, March 18, 5 pm Alaska Daylight Time

Soldotna – Matt Conner in person at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center, Ski Hill Road. Reception follows talk.

Homer – Watch Party at the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center, 95 Sterliing Hwy.

Anchorage – Watch Party at REI Community Room, 500 E. Northern Lights Blvd.

And Around the Country on Zoom

Matt Conner crossing Skilak Lake on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge in his drift boat.

It is a stressful time. Many of us struggle with less than optimum health. Join Ranger Matt Conner of the Kenai Refuge as he describes how refuges can improve our mind, body, and spirit. Matt went through a personal transformation as the result of a health crisis and is now a certified personal trainer eager to incorporate health benefits in management activities. He was instrumental in adding outdoor exercise equipment to the Kenai Refuge Multi Use Trail with the exercises tied to animal adaptations so that wildlife appreciation and exercise can go hand in hand. Interpretive panels pair the unique abilities of Alaskan wildlife, like balance and core strength, with the same physiological traits in humans. Combining his passion for nature and wildlife and a new found love of fitness training, Matt brings these two themes together in his talk.

He will also discuss the importance of nature and refuges for both physical and mental health. He is knowledgeable in the research on the effects of nature on mental health. Learn about how refuges are a source for whole foods as well as a source for mental and spiritual connection.

Skilak Lookout Trail on the Kenai Refuge provides an aerobic workout as well as stunning views and wildlife watching opportunities.

Biography

It was all because his mom would not let him have a BB gun. That is why Matt said he got into the outdoor field. He was only allowed to have a bow and arrow. By age 13 he was competing on the national level in archery. A family friend took notice of his proficiency and invited him bow hunting starting a lifelong interest in hunting and the outdoors. Matt has a Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in the human dimensions of forestry from the School of Forestry at Southern Illinois University. He worked at several national parks, the White River National Wildlife Refuge in Arkansas and the Fish and Wildlife Service Prairie Wetlands Learning Center before coming to the Kenai Refuge in 2014.

Three years ago a medical crisis changed his life. Matt utilized his scientific background to investigate the ideal lifestyle of exercise and diet to turn his health around. Along his journey he earned certifications as Personal Trainer, Nutritional Counselor and Correctional Exercise Therapy from the National Association of Sports Medicine. In addition to managing the large recreational program at the Kenai Refuge, Matt also works in his spare time as a personal trainer and volunteers at Central Peninsula Hospital in the Behavioral Health Division teaching group classes in fitness and nutrition. His life style changes have reversed his medical problems leaving him symptom free. He is a strong proponent of a healthy life style of which exercise and immersion in nature are key components.

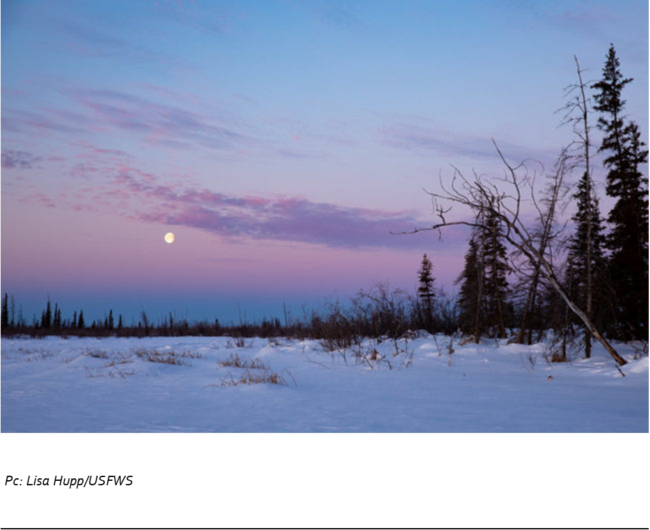

Matt is an avid fly fisherman and hiker and loves to spend his falls harvesting free range protein by stick and string!!! (bow and arrow and fly rod). He lives in Soldotna with his wife and has two grown children. Winter recreation offers serenity plus a good workout. Skiing across Dolly Varden Lake to the Dolly Varden public use cabin on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. pc. Lisa Hupp/USFWS

Winter recreation offers serenity plus a good workout. Skiing across Dolly Varden Lake to the Dolly Varden public use cabin on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. pc. Lisa Hupp/USFWS

PC for lead photo: Joseph Robertia courtesy of the Redoubt Reporter

Most of North America’s seabirds nest on this one refuge and crested auklets are some of the coolest. PC USFWS

Most of North America’s seabirds nest on this one refuge and crested auklets are some of the coolest. PC USFWS

Dan, Mist Netting birds on the river. pc Mark Lindberg

Dan, Mist Netting birds on the river. pc Mark Lindberg

‘

‘