By John Morton, retired USFWS biologist

I called Pat Walsh, the Supervisory Biologist at Togiak National Wildlife Refuge, to ask him about an interesting article he published this past year in the journal Rangifer. Titled “Influence of wolf predation on population momentum of the Nushagak Peninsula caribou herd, southwestern Alaska”, it essentially asks if wolf predation can be good for caribou.

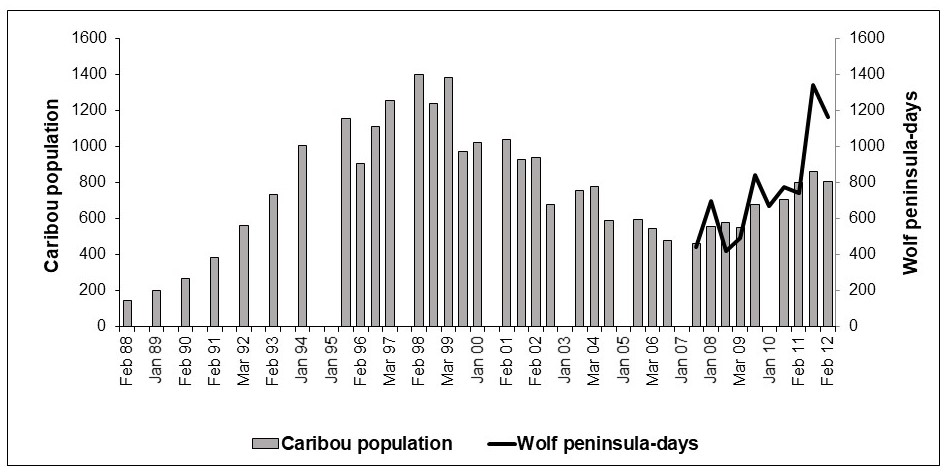

Walsh laid out a fascinating ecological story. During 1997−2007, the nonmigratory caribou herd on the Nushagak Peninsula, located within Togiak Refuge, declined from 1,400 to 500 individuals. Walsh, working closely with his Alaska Department of Fish and Game State colleague, James Woolington, investigated the time budgets of three wolf packs that used the peninsula during the following five years (2007−2012) to figure out if wolves were responsible for the herd’s decline. During their study, wolf predation steadily increased on the caribou; however, contrary to expectations, the caribou population steadily increased as well!

These two field biologists tracked 20 GPS- and VHF-collared wolves during their study. They found that only one of three packs regularly used the peninsula. This pack, known as the Ualik Lake pack, spent 35% of its time there. Its use of the peninsula was disproportionately high in late summer and fall, disproportionately low in winter, and proportional during the caribou calving season in early summer. The overall wolf use of the Nushagak Peninsula increased in direct response to increasing caribou abundance. Walsh and Woolington concluded that, in this instance, wolf predation was not driving caribou population dynamics. Instead, the caribou population was the driver and wolves were simply responding to an increasingly abundant food. The Nushagak herd had previously declined, then increased, due to internal demographic factors apparently unrelated to predation (see graph).

Not all wolf-caribou interactions are the same, and that the geography of the Nushagak Peninsula makes this situation somewhat unique. The 800 mile2 peninsula is narrow enough that this single wolf pack was able to establish its territory near the head of the peninsula, and thus defend the area from other wolves on the mainland. So, as the Nushagak caribou population increased, the Ualik Lake wolf pack spent more time preying on them, and concurrently (and ironically) spent more time protecting them from predation by other wolves! Life is not always as it seems.

Since the conclusion of their study in 2012, the caribou population has continued to increase to the point that habitat damage is evident. In short, high numbers of caribou may be eating themselves out of house and home. Wildlife managers have attempted to address this by increasing human harvest through several regulatory changes, but lack of snow in recent winters has prevented snowmachine access, which is the primary transport used by hunters there. Walsh told me, “We think it’s possible that the Nushagak Peninsula caribou will face winter food shortages in the near future, and may simply walk away”. Should this happen, local villages could lose an important subsistence resource.

Although wolf predation has not served as a very effective population control for caribou, it is certainly working in the direction of management. And to answer the question as to whether wolves can be beneficial for caribou, it appears that in this case, it could be that the protection resident wolves provide may be too much. As Walsh sees it, a bit more predation might prevent degradation of caribou habitat, which could help sustain the caribou population itself.

Walsh and Woolington wrote that the principal reason they conducted their study was to assess whether wolf population control was necessary to prevent the population decline in this herd. Had predator control been instituted at the onset of this study (as requested by local management committees), it is reasonable to believe that the caribou population would have increased as it did. However, these two seasoned biologists also point out “stakeholders might have incorrectly concluded that wolf control caused the caribou population response.” This case illustrates the importance of careful thought and having sufficient data for both ungulate and predator populations before invoking predator control.