Presented by

Robin West, Retired Biologist and 14-year manager of the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge

Tuesday, January 20, 2026, 5 pm Alaska Time

- Soldotna – Robin West in person at Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center, Ski Hill Rd. Soup supper and booksigning follows. Bring treats if able.

- Anchorage – Watch Party at REI’s Community Room, 500 E. Northern Lights Blvd.

- Homer – Watch Party at Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge Visitor Center, 95 Sterling Hwy.

- Via Zoom – link will be posted here closer to the program

From the seat of a canoe on a solo trip on the Yukon River, Robin West had time to think back on a long life and career in Alaska. Out of that experience came a book and this talk. It’s part adventure tale and part reflections on the development of national wildlife refuges in Alaska from someone who was there in that heady time when the refuges were just being created and expanded. Come hear retired biologist and long time Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Manager Robin West relive stories about his thirty-year career with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Alaska as he shares the highlights of his first book, Thirty of Forty in the 49th: Memories of a Wildlife Biologist in Alaska. The book captures Robin’s memories as he reflects back in time while on that solo canoe trip on the Upper Yukon River and into the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge in 2019, forty years after he first visited the area. The trip spawned thoughts of work accomplishments and challenges as well as created memories from this new adventure, including paddling through, and camping along the river during a massive wild fire.

Robin West in 1979 on the upper Yukon River just a year after coming to Alaska and 40 years before his solo canoe trip. PC Howard Metsker/USFWS.

Robin’s career in Alaska started during the contentious time of debate over which and how much federal lands in Alaska should be included in new or expanded refuges, parks or forests. This was prior to the passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (ANILCA) in 1980. He will include discussions of this time period and of the lasting impact of the legislation, as well as an overview of Alaska’s conservation history. His stories also will include first hand views of the evolution of national wildlife refuge management and how current issues like oil and gas development, road construction, and predator control have been addressed historically. Robin had personal experience with two of our hot button issues – he worked on the coastal plain of the Arctic Refuge now slated for oil development and was manager at Izembek where land has now been traded away for construction of a road through the heart of the refuge. Additionally, he will touch on other big topics from his tenure including the formation of agency policies, subsistence management, and climate change.

Biography in his own words

Alaska was not a place I ever imagined I would visit, let alone work for the bulk of my career. Growing up in Grants Pass, Oregon, in the 1960s, my knowledge of the 49th state was what little came from reading the encyclopedia set that held a cherished place on our bookshelf and one movie I saw at the Fairgrounds. I was intrigued, however, with science and wild animals, and I loved hunting, fishing, and visiting wild places – the wilder the better. My goal in going to Oregon State University to become a wildlife biologist was only to work somewhere with critters. While Alaska was not on my radar, when the opportunity came to go north to work after receiving my degree in Wildlife Science, I jumped at the chance. I bought a one-way ticket to Anchorage and packed my belongings into 2 suitcases, 2 cardboard apple boxes, a backpack and a rifle case. I never regretted it.

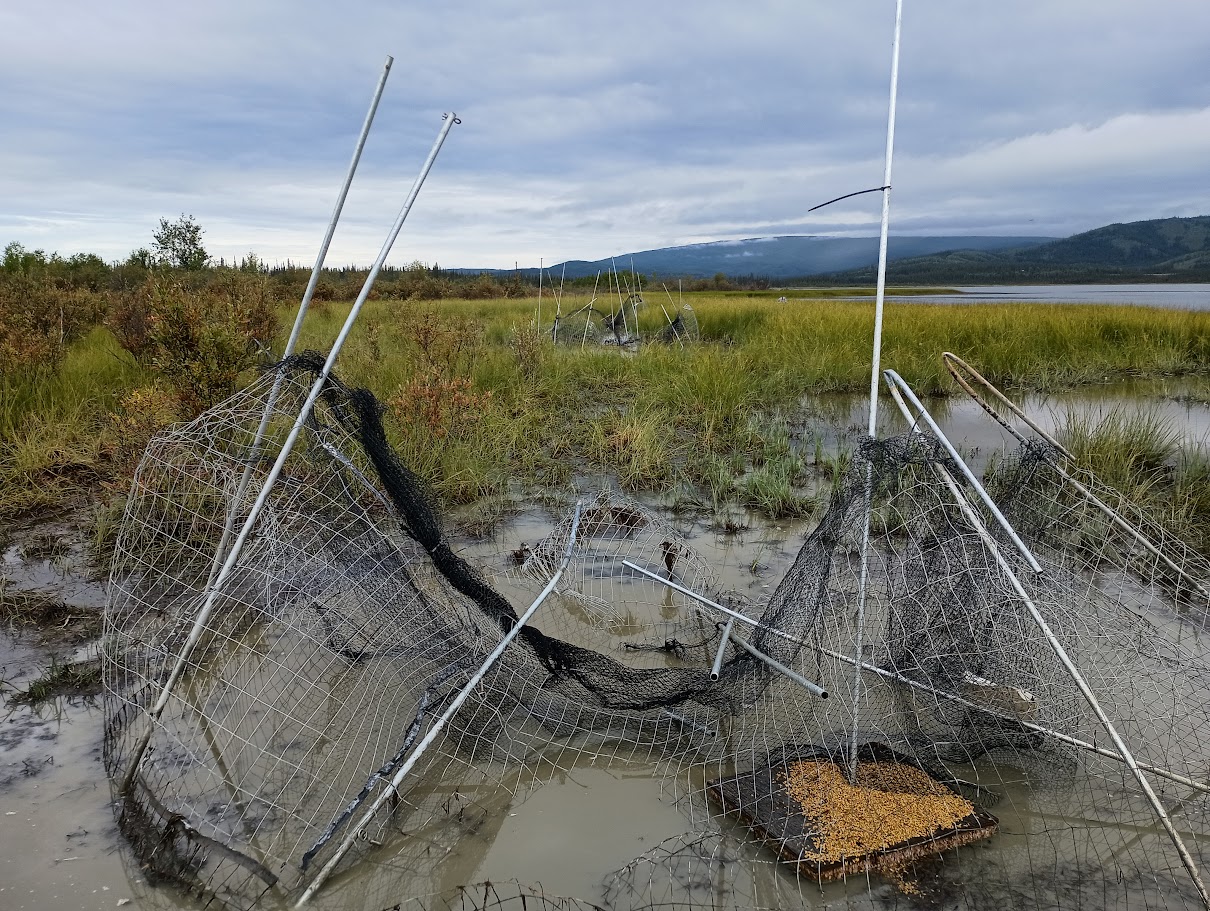

Robin West was Refuge Manager of Kenai National Wildlife Refuge for 14 years from 1995 to 2009. Sockeye salmon in Bear Creek (Tustumena Lake) on the Kenai Refuge during his years as manager. PC Gary Sonnevil/USFWS

That was in 1978 to start my career with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Alaska. For 30 years, I worked in Alaska as a contaminants biologist (working on oil and gas and mining issues), as a fisheries biologist (working in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge), Assistant Manager at Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge, Refuge Manager at Izembek Refuge, a wildlife biologist overseeing the Migratory Bird Program in the Anchorage Regional Office, and as the Refuge Manager of Kenai National Wildlife Refuge. The last five years of my career were in Portland, Oregon, retiring in 2014 as the Regional Chief of the National Wildlife Refuge System for the Pacific Region with management responsibilities for over 50 million acres of land and water.

I enjoy writing, traveling, wildlife observation and photography as well as hunting, fishing, and canoeing and continue to pursue these interests around the world, having visited all seven continents and over 40 countries. I have written three other books on wide ranging topics from a fictional work to bowhunting stories. My wife Shannon and I moved back to Alaska from Oregon in 2023 to be closer to our adult children and grandchildren and now live in Soldotna with our labradoodle “Elu”.

Photo At Top of Page: Robin at the start of his 2019 solo canoe trip at Eagle on the Yukon River. PC Alexandra Jefferies

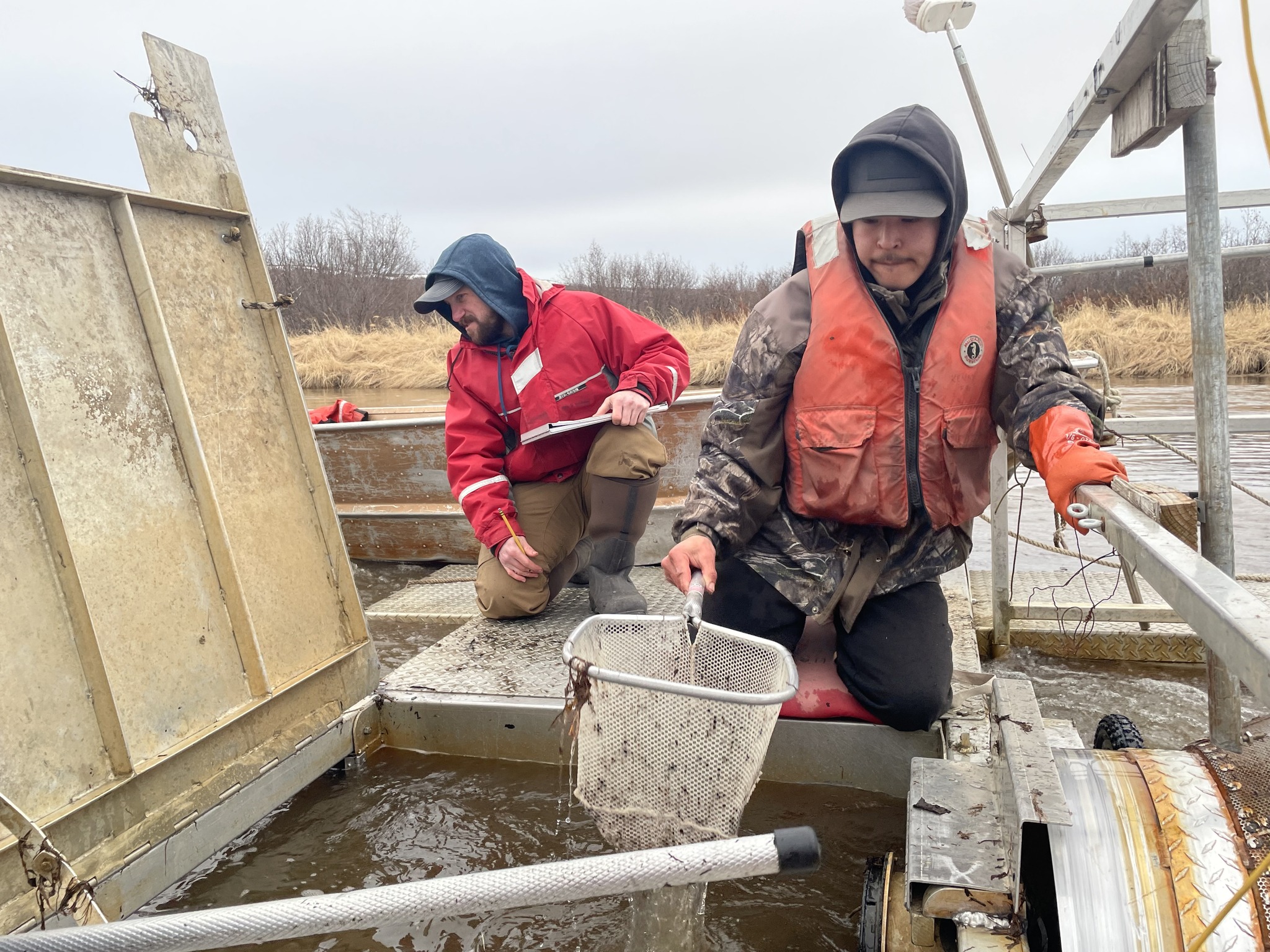

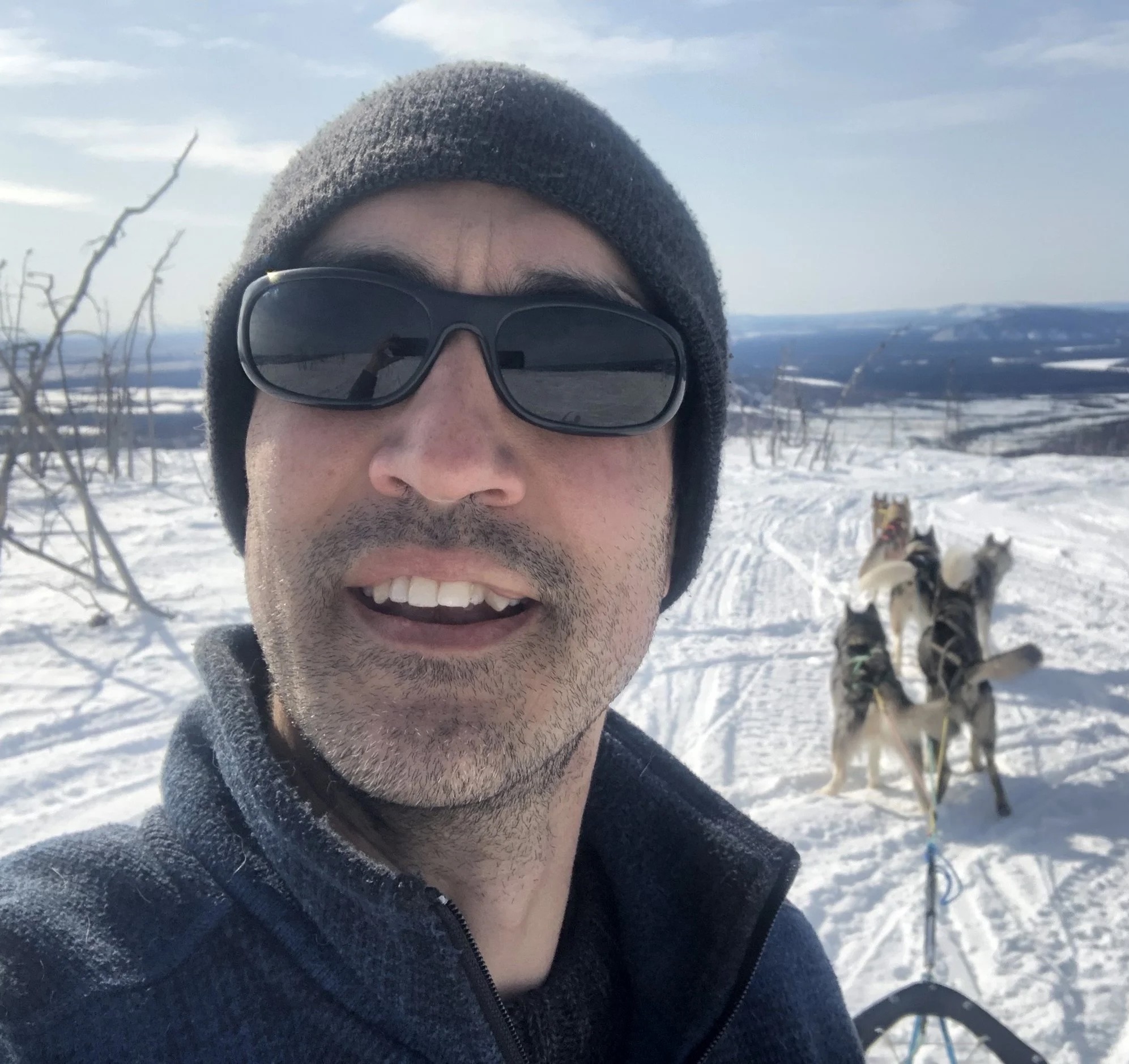

Growing up in McGrath, Kevin Whitworth learned from his elders to love the land, the river, and the natural world from an early age. He spent many hours exploring, hunting, fishing, and trapping out in the woods and on the rivers. Through high school and college, Kevin spent his summers working as a biological technician at several wildlife refuges across the state. After graduating from University of Alaska Fairbanks, he worked a number of full-time positions for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, including Deputy Refuge Manager for the Innoko National Wildlife Refuge in McGrath. Kevin has also worked for the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, and as the Lands and Natural Resources Manager for MTNT Limited, the McGrath village corporation. While working for the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, Kevin met his wife, Dara who also worked for the refuge. They have a young son and two daughters and enjoy spending time at their remote cabin, dogsledding with their team of dogs, and being outside as much as possible. He joined Kuskokwim River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission team in May 2018 and has served as Executive Director since 2022.

Growing up in McGrath, Kevin Whitworth learned from his elders to love the land, the river, and the natural world from an early age. He spent many hours exploring, hunting, fishing, and trapping out in the woods and on the rivers. Through high school and college, Kevin spent his summers working as a biological technician at several wildlife refuges across the state. After graduating from University of Alaska Fairbanks, he worked a number of full-time positions for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, including Deputy Refuge Manager for the Innoko National Wildlife Refuge in McGrath. Kevin has also worked for the Alaska Department of Natural Resources, and as the Lands and Natural Resources Manager for MTNT Limited, the McGrath village corporation. While working for the Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, Kevin met his wife, Dara who also worked for the refuge. They have a young son and two daughters and enjoy spending time at their remote cabin, dogsledding with their team of dogs, and being outside as much as possible. He joined Kuskokwim River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission team in May 2018 and has served as Executive Director since 2022.