by Patricia Heglund, Homer Friend and retired USFWS Biologist

Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.- Margaret Mead

Jim King was one of those people who changed the world. Alaska’s National Wildlife Refuges lost a staunch advocate and conservation leader with his death in March at home in Juneau at the age of 97. Jim was such a gift to me when I was starting my graduate work and throughout the remainder of my life. Jim’s remarkable life and many awards and achievements are documented in a touching memorial from his family and a Fish and Wildlife tribute. I’d like to focus on one place and a couple of stories to help Friends better understand the significance of Jim’s work.

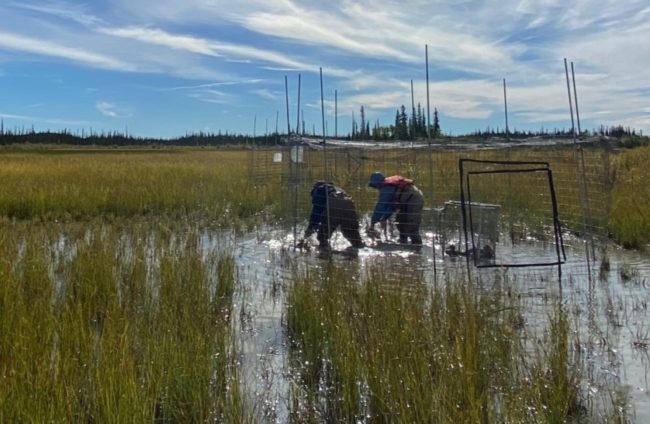

I met Jim King in 1984 when I was a graduate student planning to conduct research on the new, Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge. Jim had a special knowledge of and affection for the Yukon Flats. He and his wife Mary Lou honeymooned at Fort Yukon while Jim flew aerial surveys and banded waterfowl. The work was for an environmental study of the potential effects of building a hydroelectric dam on the Yukon River at Rampart Canyon. As proposed, the dam would have flooded nine Alaska Native villages and tens of thousands of wetlands that were breeding grounds for 1 – 2 million ducks, geese and swans. The dam would have created a lake about the size of Lake Erie. Waterfowl that Jim and others banded at big lakes on the Yukon Flats, like Ohtig and Canvasback, were harvested in 46 states and over half of the Canadian Provinces. Based in part on Jim’s work, the US Fish and Wildlife Service strongly opposed dam construction and in 1967, Morris Udall, Secretary of the Interior, voiced his opposition to the dam. The project was canceled in 1971 eliminating the immediate threat to the people and waterfowl of the Flats and allowing for a different future for the land as a National Wildlife Refuge. Jim King piloting N754 on a waterfowl survey. I was so inspired by flying with Jim that I got my pilot’s license.

Jim King piloting N754 on a waterfowl survey. I was so inspired by flying with Jim that I got my pilot’s license.

Jim once told me a story of how he, and maybe others, photographed several areas of Alaska from his plane using a simple point and shoot camera. He created a picture book of recommended refuges, adding descriptions of the locations and details on the use of the area by breeding waterfowl. Jim took his book to Washington DC to the Secretary of the Interior. In 1980, several of the areas he documented were added to the National Wildlife Refuge System by President Jimmy Carter. I remember being amazed at how accessible someone like the Secretary of the Interior was to a flyway biologist back in the 1970’s.

Jim King (right) and Bruce Conant taking a lunch break on the wing of N754, a deHavilland Beaver modified specifically for low level (less than 500 feet) wildlife surveys by the Fish & Wildlife Service. This legendary plane, well-known all-over bush Alaska for over 35 years, now hangs in the Anchorage airport.

Jim’s and my friendship continued over the years. Jim hosted me at his house on Sunny Point and introduced me to his dear wife, Mary Lou, and their menagerie of waterfowl. In more recent years, Jim and I sat on a panel reviewing the biological program at Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge. Jim always sent me copies of his latest publications, including his last book, Attending Alaska’s Birds, fascinating reading for anyone who appreciates the history of Alaska. I last saw him at his home in 2019 when on his urging I finally brought my family to meet him. Jim was developing dementia and I don’t think he really knew who I was. But nevertheless, Jim and Mary Lou welcomed us graciously. It’s hard to think of Jim as gone. When I think of him, I see him in a western-style shirt, scrimshawed bolo tie around his neck, smiling, relentless in his pursuit of conservation. I am grateful to have known him.